It wasn’t intentional, but we arrived in Taipei just in time for the “Quemoy Matsu Crisis” of August, 1958. Briefly, “Red” China was shelling off-shore islands that belonged to Taiwan (still at that time called Formosa by most). We stayed at the Friends of China Club, a well-known hotel located directly across from Chiang’s headquarters, the MND building. Our flight also brought a number of reporters who were covering the crisis, who also stayed at the FOCC. They couldn’t actually go anywhere close to the action, so most of the dispatches were probably written in the FOCC bar.

In those days the US still had a significant presence in Taiwan. One of the Army’s Military Assistance Advisory Groups (MAAG) was headquartered in Taipei, there was an air base in Tainan, and my father’s unit, NAMRU-2 (Naval Medical Research Group 2) was located in Taipei, continuing the Navy’s proud tradition in tropical medical research. As quasi military dependents, we could shop at the PX, go to the Naval Officer’s Club, and go to movies, restaurants, etc. at the base when we needed a dose of home.

Mary and I attended the Taipei American School, a private school staffed by Air Force teachers, and catering to the military, diplomats, an American missionary or two, and the children of ambitious Chinese families who wanted their children to learn English. This was extreme cultural dissonance for Mary and me, but after a bit of homesickness, we settled in. The school was excellent, we made friends, and my Pop bought an old green Dodge that we used to explore the island on weekends.

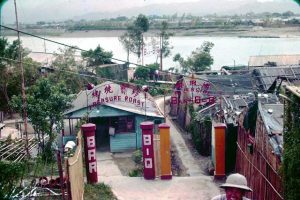

Food was a big deal. Both of my parents were adventurous eaters, so we took full advantage of the opportunities. My father joined a lunch get-together group called the Chow Chow C lub, that would partake of local eateries, and then he would take us to the ones he especially liked. One of the highlights, remembered fondly by all who were there in the late 50s was an establishment called the Riverside BBQ, pictured to the left. This was an outdoor restaurant consisting of a covered but open-air space with a large buffet of raw ingredients (sliced meats, veggies, various sauces and spices) which diners could combine as they wished. With repeated visits, diners developed a recipe – more garlic, some ginger water, lots of cilantro,… When satisfied they took their creations to a cook at a domed charcoal grill, who would proceed to quickly stir fry the ingredients and return them. Diners would consume their concoction with rice, sesame buns called shaobing, local beer, or a soft drink called ChiSue, something like 7-Up. (Following service people back to the US after the Viet Nam era, similar cuisine appeared as Mongolian BBQ in several US cities).

lub, that would partake of local eateries, and then he would take us to the ones he especially liked. One of the highlights, remembered fondly by all who were there in the late 50s was an establishment called the Riverside BBQ, pictured to the left. This was an outdoor restaurant consisting of a covered but open-air space with a large buffet of raw ingredients (sliced meats, veggies, various sauces and spices) which diners could combine as they wished. With repeated visits, diners developed a recipe – more garlic, some ginger water, lots of cilantro,… When satisfied they took their creations to a cook at a domed charcoal grill, who would proceed to quickly stir fry the ingredients and return them. Diners would consume their concoction with rice, sesame buns called shaobing, local beer, or a soft drink called ChiSue, something like 7-Up. (Following service people back to the US after the Viet Nam era, similar cuisine appeared as Mongolian BBQ in several US cities).

I’ve gone into this much detail to set the stage for Anne abroad. On the one hand, she was a “military” wife. In those days, the wives of officers were expected to lead a genteel existence in support of their officer/gentleman husbands, hosting luncheons, teas, etc. This was not my mother. Once we were settled in our house in Shin Yi Lu, nestled among rice paddies and looking up at the hills east of Taipei, Mom began her explorations. Not for us a retiring housemaid (called an amah in Taipei). Our amah, Asi Yu, cooked with Mom, ate at the table with us, and accompanied Mom to the market to buy produce. Learning about a teacher of Chinese watercolor painting, Mom signed up for lessons and was soon turning out scroll after scroll. She did host one memorable costume party for Pop’s NAMRU associates, but basically avoided the military as much as she could.

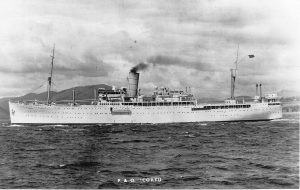

But, it didn’t last, and by early 1959 my parents had decided to give it up. The plan was for we three to return to the US in late May. As civilian dependents, we had two options – first class back the way we came, or tourist any way we wanted to go. My mom opted for the latter, of course, and booked passage on a British ship operated by the Pacific and Orient company called the SS Corfu. The ship was to leave from Hong Kong, and arrive, one month later, in Southampton.

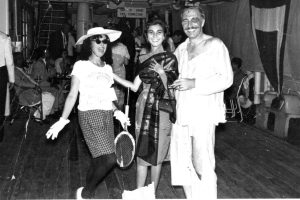

Ah, the Corfu. Built in 1918, it carried passengers and cargo. The itinerary was as follows – Hong Kong, Singapore, Penang, Columbo, Bombay, Aden, Port Said and thence to Southampton. A veritable tour of the Empire, then in decline. Passengers in tourist class included Brits returning from assignments overseas, other colonials returning home, and a few working girls. Mom loved it. There really wasn’t much to do except to visit with other passengers in the lounge, and Mom quickly joined up with a gentleman returning from military service in Malaya, and a young Eurasian woman moving to London to start a career. There was also a retiring deep sea diver from Ireland who was returning home because his wife, who hadn’t seen him in years, had threatened to divorce him. And another Irish lad reputedly with IRA connections, who seemed to drink a bit. A real cross section.

Between Bombay and Aden, crossing the Indian Ocean, we encountered a typhoon, a real experience in a smallish steamer like the Corfu. Attendance in the dining room was very sparse, but we three, descendants of the sea-faring Uren family (Urens do not get sea-sick, we were told) missed not a meal.

We were met in Southampton by my mother’s uncle Bernie, grandson of the same JG Uren described elsewhere. Bernie had managed to rise to European vice president of American Express, having started as a tour guide in Egypt in the 1930s. He and wife Kaye lived in a beautiful flat near Hyde Park, and had a butler and a chauffeur. It was a perfect introduction to London for me and my sister.

We proceeded through Cornwall to the Scilly Islands, staying with various relatives along the way: Banfields in East Looe and Redruth, and then another Banfield, my mother’s cousin Roger, at Holy Vale in Scilly. Mom had been to Scilly when she was 7 or so, but having heard so much about the islands and the family history there all her life from her parents, this was a real highlight, as was meeting these close relatives. This was just before Scilly became a tourist destination. It was still remote enough to retain a lot of Cornish charm, and better yet, rested in the Gulf Stream. We all thought it was a bit of paradise.

We proceeded through Cornwall to the Scilly Islands, staying with various relatives along the way: Banfields in East Looe and Redruth, and then another Banfield, my mother’s cousin Roger, at Holy Vale in Scilly. Mom had been to Scilly when she was 7 or so, but having heard so much about the islands and the family history there all her life from her parents, this was a real highlight, as was meeting these close relatives. This was just before Scilly became a tourist destination. It was still remote enough to retain a lot of Cornish charm, and better yet, rested in the Gulf Stream. We all thought it was a bit of paradise.

Back in the US in August of 1959, we returned to Evanston, and my mother embarked on her new life as a divorced provider. She returned to the synagogue, working for Rabbi Polish, but things were changing. There was a new business manager, a capital campaign to build a new temple, and although my mother kept up all her friendships, she decided it was time to move on.

By now she had established herself as a skilled executive secretary, and had no trouble finding decent jobs. She was pretty, personable, smart and hard-working. Her first post-synagogue job was as secretary to the head of the Evanston Health Department. I think this was one of her favorite jobs. The work was useful, her co-workers congenial. I remember two in particular. Ronnie Laurent was a very personable and articulate person who happened to be Black. He it was who introduced me to WEB Du Bois. He was a regular at Mom’s get togethers. Another co-worker, whose name I have lost, was also a divorced mother, who was struggling with dating, but had a more adventurous spirit.

Mary and I finished middle school at Nichols Junior High School, and proceeded to Evanston Township High School. I remember being called in to talk to a counselor, who mentioned that the summons was due to my mother’s being divorced, not common at that time and a cause for concern. My loyalty kicked in and I denied that there was an impact of any sort. Much later, in therapy, I acknowledged that there were effects, some of which lasted for years. A similar encounter at Northwestern was handled in the same way. Two chances missed.

As High School proceeded, I found myself becoming a support of sorts for Mom. I was precocious and smart, and appeared to be more mature than I actually was. Over time Mom became more open about her relationships with the various men that she dated. My role was to back her up, provide encouragement, and help her face a world that caused her to be anxious. A part of me is still proud that I was able to do this, and it established support and empathy as skills in my repertoire, but, again in therapy I learned that there was a price. But, overall this close relationship was important to both of us. Mom was able, with Pop’s assistance, to provide most of what we wanted, and everything we needed, no small accomplishment on a secretary’s income.

At one point, after attending a Lakeview High School reunion, Mom started dating another graduate, and after a very brief period, they decided to get married. We moved to a bigger apartment, and WBR (as we called him) moved in. This did not work out well. WBR was not a match for Mom, and Mary and I did not make it easy for him to fit in. The marriage self-destructed in a matter of months, and it was back to the three of us.

As Mary and I moved on from ETHS, Mom decided to complete her degree, hoping no doubt to move past the sort of condescension that was a part of secretarial work. She enrolled at Chicago Teacher’s College (later Northeastern Illinois) in education, attending classes during the day while working at Evanston Hospital at night, and not sleeping a lot. Classes went well, but she couldn’t quite make the money work. After being turned down for a loan by my (rich) uncle George, she had to stop studies short of a degree.

Mom had lots of friends, many from the Unitarian Church in Evanston. She also experimented with other churches, at one period becoming involved with a very diverse Baha’i group. Fellow students at Eastern, and one Anthro professor in particular, became guests. Others included members of a group of poets who had started a small local journal. Always eclectic and interesting, Mom’s friends were.

By this time Mary and I had left home, so she moved from Evanston to Rogers Park, and secured a job as secretary to Orlando Wilson, the well known superintendent of the Chicago Police Department. This was an adventure. She took a course in forensic methods, and even dated a cop. But eventually, as the counter culture kicked in, and I especially was an enthusiastic participant therein, she became disenchanted with CPD. She decided to leave Chicago, and moved to Champaign, where she could be closer to Mary and me.

As always, she was experimenting. She was still working as a secretary, but not having to support the kids, she had enough resources. I think she had given up on men. While in Champaign, she agreed to house her sister Ethel, who had been released from a mental hospital. Ethel was her older sister, had one son, and had become an alcoholic, eventually developing a severe mental illness. This was the late 60s, at which time psychotropic drugs were just becoming an option. She had been able to stabilize on one drug and was released, but her husband had his own problems, so Mom agreed to take her in.

As always, she was experimenting. She was still working as a secretary, but not having to support the kids, she had enough resources. I think she had given up on men. While in Champaign, she agreed to house her sister Ethel, who had been released from a mental hospital. Ethel was her older sister, had one son, and had become an alcoholic, eventually developing a severe mental illness. This was the late 60s, at which time psychotropic drugs were just becoming an option. She had been able to stabilize on one drug and was released, but her husband had his own problems, so Mom agreed to take her in.

This did not work out well. Ethel stopped taking her meds, and relapsed. After getting her back, sort of, on the meds (with help from her counter culture son who could get his hands on Thorazine), Mom decided to move with Ethel down to Florida to live with their father Jack. (Jack is described in another post here). Ethel continued to struggle, and was forced to return to an institution in New York. Mom and Jack shared an apartment for a year or so, but eventually decided that he should return to his own space.

Professionally, this was probably the best period of Mom’s career. She started at University Hospital (now UF Health), working evenings in the ER as a supervisor. Her organizational skills quickly became apparent, and her job was re-cast as what we would now call a process analyst, developing procedures for patient management. I’ve always thought of this in a couple of ways. First, good for her, and good for the hospital for having recognized her skills. And second, how ironic is it that she ended up doing what her son (me!) ended up doing. I had a credential, and made more money, but she enjoyed the work, made a little more money, and finally (finally!) was doing work that employed more of her talents.

But unfortunately, she was at this point approaching sixty, and a lifetime smoking habit had begun to catch up with her. Walking became more and more difficult, and she retired when she reached her sixty third birthday in 1980. I had noticed her frailty when she visited Champaign for my first wedding in 1979, when brother in law Mike McLean had to carry her up some stairs to my apartment. So I was shocked, but not really surprised when in 1984 I received a call at work from the ICU department at University Hospital. Mom had been admitted with congestive heart failure. I rushed down to Jacksonville, and was joined by sister Mary, who was living in London.

But unfortunately, she was at this point approaching sixty, and a lifetime smoking habit had begun to catch up with her. Walking became more and more difficult, and she retired when she reached her sixty third birthday in 1980. I had noticed her frailty when she visited Champaign for my first wedding in 1979, when brother in law Mike McLean had to carry her up some stairs to my apartment. So I was shocked, but not really surprised when in 1984 I received a call at work from the ICU department at University Hospital. Mom had been admitted with congestive heart failure. I rushed down to Jacksonville, and was joined by sister Mary, who was living in London.

Mom had always had a complex relationship with doctors. Like many contemporaries, and in spite of having worked in several hospitals, she just didn’t trust them. She had been very clear with us that there were to be absolutely NO heroic measures, and had underlined this firm feeling by joining the Hemlock Society, an organization that supported physician assisted suicide. By the time I arrived, Mom had already been intubated and was unconscious on a respirator. The nurse told me that she had resisted the intubation, but they had proceeded, not having any other guidance.

Ah, the complexity. Had the directives been clearer, or had I been there, I’m not sure what would have transpired. In any case, when she came to after a day or so, I think she was OK with having survived. Mary and I stayed with her for several days, until she could go home, and the hospital social worker had arranged for a caretaker to help her adjust.

Ah, the complexity. Had the directives been clearer, or had I been there, I’m not sure what would have transpired. In any case, when she came to after a day or so, I think she was OK with having survived. Mary and I stayed with her for several days, until she could go home, and the hospital social worker had arranged for a caretaker to help her adjust.

Post-crisis, I think Mom was happy, or at least resigned. One of the interns discussed her feelings about treatment with us, and told us that it was not uncommon for people with strong opinions like Mom’s to change their minds after a close call. One of her visitors was a Baptist minister who served as a chaplain. He was youngish, not pushy, and actually open to discussion. When he asked Mom what religion she was, she paused, thought a bit, and then replied “Well, I guess I’m a lapsed Unitarian”. Following another pause, we all broke up at the novelty of such a denomination, and she and the minister became buddies. It turned out that he had had doubts, and he ultimately left his church.

After she was settled back in her apartment, it was clear that she needed someone close, so she agreed to move back to Chicago. I found her a studio apartment on Sheridan Road and furnished it, then went back to Jacksonville to close down the apartment and accompany her back. She stayed with me in Lakeview for a couple of weeks to re-adjust while I completed arrangements and she accustomed herself to living with an oxygen concentrator. And then, into her new place, which she liked.

She lived as an invalid until 1990. She had arranged for a cleaning lady who would also do her shopping. I would come over a couple of times per week, make minor repairs, etc. and I also took her to her doctor’s appointments. She read, watched TV, and seemed to be comfortable for the six years she lived there. One day in 1990, I called as usual around lunchtime, and there was no answer. After one other call went unanswered, I knew something was wrong, so I went to her apartment. She was sitting in her usual place on the couch, TV on, next to a simple breakfast. She had apparently passed in the morning sometime. The death certificate was not specific, but the doctor thought it was probably her heart. She was 72.

We had a small memorial for her at the funeral home. Among the people who came was her old friend Rabbi Polish, whom I had been able to contact, as well as another old friend, Terri Costan, whom she had known at the Unitarian Church. It was a warm and quiet affair, with a few laughs thrown in.

I still have her ashes, which she wanted to have scattered from a particularly scenic place (Penninis Head, pictured below) in Scilly. Linda and I do intend to go to Scilly, so I should be able to satisfy her wish. And strangely enough, I also have my father Quentin’s ashes on the same shelf in my closet. Some of his ashes, at his request, went to Thailand with second wife Boon Nam, but he also wanted ashes scattered on his mother’s grave in Kansas, which Mary and I have discussed doing together. I’m definitely not a believer, and I know there’s no communication, but I can’t help wondering what they would think of this arrangement. I hope they’re patient.