After years of talking about it, Rick and I set off to explore Cornwall on June 25, 2023 with a tentative three week plan. Ahead of time, I did some fact-finding: Cornwall is a county on the southwest peninsula of England historically identified as Cornish, with about 570,000 residents and a 422-mile rocky coastline exposed to the sometimes gale-force winds off the Atlantic. The Duke of Cornwall has owned most of this land since the 14th century, and he also owns about a third of its residential buildings. Cornwall’s climate is the mildest in Britain: the gulf stream moderates temperatures to the 50s much of the year.

Sounds good, but what would we find there? At our somewhat advanced age, could we still navigate the up and down stony trails? Would we find crowds everywhere, as several websites warned? What about driving on those narrow winding roads?

Rick had visited Cornwall with his mom and sister in 1958 when they returned by ship from their year in Taiwan, where Rick’s dad was working for the U.S. Navy. Last spring Rick put together the slides from that 1958 visit to his Cornish great aunts and uncles who hosted them then, black and whites of stone houses and cobbled streets, most on the Scilly Islands off the coast of Penzance.

So revisiting those sights helped us form the plan, and here is what resulted.

First Impressions. Arriving in London Rick and I, two sleepy, no-longer-youthful passengers with suitcases and backpacks, found our way through Heathrow’s throngs to a commuter shuttle to Paddington Station. From there we squished onto a crowded train, bags piled inside boarding area, backpacks under seats as we journeyed down Cornwall’s east coast to Penzance, the last stop. We debarked onto its beachfront walkway into cool, fresh air, wheeling our bags on the long promenade overlooking the rough ocean water. Quiet, lean, often white-haired older couples in windbreakers and rubber-soled shoes walked their equally quiet, well-behaved dogs, or, from the stony beach, threw balls into the water for their dogs to fetch and return. It all felt peaceful, not crowded. We passed a lawn bowling court, native plant garden, picnic area, playground, skateboard ramp, dog run, stalls selling food, and on the water a few swimmers and kayakers as we walked to our lodging at The Beach Club. The next morning, at the bay window of our lodging, rested and surrounded by sun, water, and sky with a perfectly arranged plate of strawberries, raspberries and dried apricots in front of us, I promised myself to NOTICE and to CELEBRATE the small moments of each day. One arrived later that afternoon when we sat, relaxed and happy on the edge of the Penzance dock, sharing our first English pasties with local seagulls.

Exploring Scilly. The next day our ferry, the Scillonian III, took us on a restful 2 hour ride from Penzance to Hugh Town on St. Mary’s, the largest of the Scilly Islands about 30 miles off the east coast. On board with us were many families, and quite a few elder travelers enjoying the journey, again with their obedient dogs. When we learned that we could have our luggage delivered directly from the dock at Hugh Town to our lodging, we decided to hike the island’s coast trail. As we negotiated the rugged, narrow trail, rain lashed our faces, the wind was fierce, and dramatic granite rock outcroppings appeared, one after another: Penninis Head, the Islands’ southernmost point; Cairn Michael; and Pulpit Rock, a thick slab of granite leaning out on the waves lashing below It. I could easily imagine the need for the Penninis Head Lighthouse, completed in 1911 and still in use. Cold and dripping wet we arrived at our lodging, the Old Town Inn. Our bags awaited us, and the new owners welcomed us to our comfortably accommodated room, complete with microwave, refrigerator, coffee and tea makings, utensils, and packets of dry cereal which we extended with milk, yogurt and nectarines from the local market. In the evenings the owners, just in their 30s, hosted informal musical gatherings that extended into the courtyard outside our room. Still, we slept very well!

Holy Vale. A mile walk from the Inn led us along narrow roads past small, well-tended cottages, many with hydrangeas, bird feeders, wind chimes, or green farm fields, to Rick’s mother’s family’s former homestead, a several-acre site which had been a flower farm providing fresh flowers to England’s mainland and is now a winery, in a secluded little valley called Holy Vale, still with many blooming azaleas and hydrangeas. The ivy-covered stone residence where Rick’s grandmother Blanche had lived is still in use, with its original front stone wall and iron gate hung with vines. Holy Vale, we learned, had once been a homestead for many newly-settling Methodists, who had been converted by John Wesley in the 1770s. With his emphasis on

good works, Wesley began Methodism as a variation of the Church of England, but broke away to form his own church. Later Baptists moved into Holy Vale too, and some lively religious discussions ensued. Rick learned that his ancestors, the Banfields and the Mumfords, had lived in these religious communities.

Great Grandmother Ethel. Another short walk from our Old Town Inn, in a graveyard on a hillside overlooking a bay, Rick found the memorial stone honoring his great grandmother Ethel. Ethel too was a native Scillonian, but after giving birth to Rick’s grandfather Jack, died in Shanghai at age 25; her husband, Rick’s great grandfather Gilbert, had been laying cables there for the British government linking China to Indonesia at the time his wife died. To fulfill Rick’s mother Anne’s request, Rick scattered her ashes, which he had saved since his mom died in 1990, around the memorial stone. The small Church of England in the graveyard had a “1642” headstone, and inside were well-used hymnals from the 1920s, still serviceable. Former PM Harold Wilson is buried on the hillside there.

Another tombstone honored Alexander Smith, who had controlled the leases on Scilly property in the 1800s. From the cemetery we had a clear view over the bay to the Scilly island airport where a private plane took off as we watched, a jarring reminder of the modern world.

Ancient landmarks. Scilly’s narrow, steep island trails, lined with prickly gorse, looked out on treeless hillsides blooming with heather, fennel, and bears’ ears. On a hillside we passed the rocky remains of at least one village dating from 1300 BC. Before Falmouth became a major port, these Scilly Islands were a popular stopping off place for ships from Europe and the Far East, so even in ancient times trade in spices, wine, fruit, and oil was already flourishing. The sea yielded fish, the land fertile enough to grow wheat, oats and barley on the terraced hillside. Skulls and pottery remnants from the village resurrected in 1900

suggested that these early inhabitants had led “sophisticated lives.” Shards of Roman pottery dating from 43-400 AD have been found on neighboring Nemours Island.

The windy, invigorating trail led us past the Giant’s Cave, a large granite outcropping, and Rick sat for a “photo opportunity” in an odd-shaped megalith called the Druid’s Chair. Twists in the trail led us past dramatic caves, stony beaches, abandoned tin mines, pounding surf. A few fishing boats braved the lashing waves, but it was easy to see how ships could come aground on the forbidding rocks.

Britain and Telegraphy. Back in Penzance three days later, Rick found the house where his great, great grandfather John, who called himself JG, had lived. He had been the postmaster of Penzance and in that role was involved in the first telegraphy, which was established at all the British post offices during his tenure.

We visited the Museum of Telecommunications at Porthcurno outside Penzance. A docent educated us

on the basics: a wire with an electric charge can send a signal that can be controlled, on or off, over a distance. Code the alphabet and numbers into dot-dash symbols, as Samuel Morse did, with pauses between letters and longer pauses between words, send a coded message on the wire. Train people to send and to transcribe messages at each end of the wire. If the message needs to go over a long distance separated by water, bundle the wires and surround them with gutta percha to insulate them, then drop the protected wires into the water, regenerate the signal at points along the wire, and “siphon” it with glass so you have a copy of the message and someone to verify it. The first cables stretched from Porthcurno to India in 1870, and after that cables were linked to South Africa, Portugal, and the U.S. By the end of WWII fewer humans were needed: messages could be typed on a typewriter that automatically sent them to a machine that transcribed them. In the 1980s came fiber optic cable, a visual laser signal faster and with more messaging capability; light moves more quickly than sound. At the museum I enjoyed practicing sending a message using Morse Code and touring the underground tunnel used to protect the equipment during World War II.

Rick’s great great grandfather JG, the former postmaster, wrote a book about his experiences with telegraphy and the initial laying of the cables, including a vivid description of the first cable linking Penzance and the Scilly islands – and Rick has one of the original copies of that book.

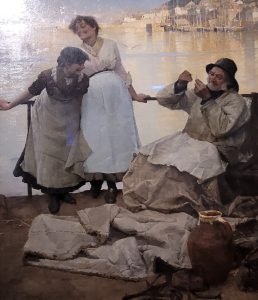

The Newlyn School. Another of Rick’s relatives, Walter Langley, initiated what is now called the Newlyn School of Art in the 1880s, with a focus on

unposed, “plein air” scenes. Soon he was joined by Stanhope Forbes and his wife Elizabeth, who opened the school. In a restored Penzance mansion we toured the Penlee Gallery that exhibits works from this Newlyn School (Newlyn is the next village south of Penzance.) Many paintings were set in the nearby Lamona Valley, sunlit scenes of young families, fishermen, card players, children at play, cows, farm fields, water and sky, the young people that were part of the movement. It’s so easy to imagine the pleasure of that time – falling in love with each other, starting their families. Walter Langley married one of Rick’s great aunts.

Morab Gardens. We emerged from the exhibit into afternoon sun and walked to the nearby Morab Gardens, again blooming with hydrangeas, rhododendron, Rose Campion and many palms! Like Bordeaux in France, Cornwall is considered subtropical and can grow many varieties that cannot thrive on the mainland. The Garden had a gazebo at its center with benches here and there among the plantings. A Dixieland jazz band played in the gazebo as a yogi danced to his own rhythm; dogs and their owners meandered peacefully along the paths. The Newlyn painters would have had their easels and brushes out!

The Scary Left Lane. After our week in Penzance/Newlyn we rented a 2-seater Fiat, uneasy moments as Rick got used to driving on the left, large trucks approaching on winding roads sometimes lined with stone fences, roundabouts with confusing signage…but he figured it out after the first nail-biting day and we made a little circuit that allowed us to visit Jamaica Inn, the moors, and several Cornish towns.

Smuggling. Beginning in the 1770s Jamaica Inn,

on the Bodwin Moor, became a hangout for smugglers and their goods. New duties on tobacco, tea, brandy, rum, silks, muslins, sugar, handkerchiefs, and salt were so prohibitive then that they almost encouraged smugglers to do their worst. Smugglers learned where the arriving ships were most likely to come aground, and if they were brutal, killed the captains and crew. They hid their bounty in the deep recesses of Cornwall’s coastal caves, then moved it by donkey or horse to a hideaway, often in the dank basement of the Jamaica Inn. The bleak, barren moors were a perfect hiding spot, with no arable land for miles around, only a few cattle. Most people were so poor then that they didn’t complain much about smugglers; it became a career for many struggling Cornish fishermen, hoping they might profit themselves if a ship came aground near them. Even church rectors would often hide smuggled goods in their churches for later redistribution.

The Jamaica Inn museum clarified all this, and has a large section honoring Daphne Du Maurier, whose book, Jamaica Inn, gives readers a vivid picture of the smugglers’ greed, desperation, and brutality, brought to a dramatic confrontation with the profiteers at the Inn.

Exploring the moors, sort of. We shared a cheese platter at the Inn, then tried hiking from its parking lot to “Brown Willy”, what looked like a modest nearby moor. Its treeless, windswept granite hill seemed to rise gently, but as we continued walking toward it, it seemed to move away from us! So after a mile or two of continuous, wearying uphill walking we sighed and settled into a hillside near a few cows in a farm field as we watched younger backpackers wind their way up the windy moor. Okay, so maybe we ARE too old for a few things.

Wandering in Wadebridge, Looe, and Falmouth. Rick had stayed with great aunts and uncles in all three of these in 1958. Wadebridge is a

peaceful, quiet riverside village with a long, mercifully flat walk linking it to Padstow along the Camel River, with egrets, gulls, and avocets pecking in the shallow mud flats. Oaks on the trail formed overhanging arches. Over the river in the village was “the old bridge”, its headstone dated 1468, honoring the wool trade.

Looe sits on the winding Looe River which we also explored one rainy afternoon. I had been reading aloud from Julian Barnes’ reflections on choices as you face the end of your life, and it focused our conversation as we sat at the river’s water gate. Mostly, we decided, we wanted to clean the basement! Our genial hosts in Looe were delighted to learn of Rick’s Cornish roots and prepared for him the most enormous, complete English breakfast I had ever seen.

In Falmouth we found a busy seaport and many Falmouth University students, its streets lined with vintage clothing stores and lively restaurants along

the waterfront. Falmouth is Britain’s farthest-south deep water port, and its harbor was busy with two large navy ships, pleasure and fishing boats moving in and out, and a healthy collection of seabirds. One pigeon seemed to be trying to lay an egg as we observed her from the dock.

At Falmouth’s Maritime Museum we learned more about the lucrative business of Packet Boats that operated between 1688 and 1850. “Packets” were envelopes of cash that could be sent by ships, called “packet boats”, to recipients in distant ports. The packets were placed in the trust of the ship’s captain, who received a “cut” in exchange for arranging for delivery of the packets. This grew into big business as international trade with Britain expanded; captains became wealthy, including Samuel Cunard who, in 1839, got the first British government contract to supply a regular mail service across the north Atlantic. Some captains were scoundrels. A map illustrated the routes linking Falmouth to Lisbon, Madiera, Barbados, Jamaica, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Charleston, New York, Halifax, and other ports. The museum illustrated the closet-size space, barely enough to hold a pot, allotted to workers on those early ships. One of these packet boat crewmen was Rick’s great, great, great grandfather Joseph.

Rainy London with the Rossettis. Back at Penzance we returned our trusty Fiat, then boarded the same coastline train for our five hour northeastern journey. The coastal villages appeared as we rode, becoming more and more urban as we neared London. From Paddington Station we wheeled our bags the half mile to our lodging off Bayswater Road adjacent to London’s Kensington Gardens. We discovered a delicious, convivial Greek restaurant called Haleda only a few blocks away. It was packed with customers, but the manager found space for us “for one hour” and seated us where we could observe the busy chef, the animated conversations, the waiters moving skillfully amid the crowded tables. Lively! Lamb kebab and rice for Rick, a Greek salad for me, then a walk in the Kensington Gardens.

The next morning, on Bastille Day, in a drizzle that became nearly a downpour, we bundled in our fleece windbreakers to walk the 4.5 soggy miles from our hotel through Kensington Gardens, under Wellington Arch, through Hyde Park and the Serpentine past Buckingham Palace in time to witness marching guardsmen and a big crowd huddled under umbrellas, but we missed the changing of the guard.

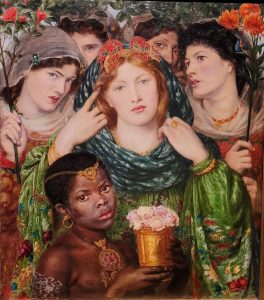

Arriving at the Tate, we dried our jackets using the restroom’s hand dryers before we took in the extensive Rossetti exhibit of the lives and works of

Maria, Gabriel, William, and Christina, and their complicated circle of Rossetti family entanglements.

The four Rossetti children were born between 1827 and 1830 and grew up in mid century London. Their parents, scholars of Italian heritage, encouraged them as writers and artists. Gabriel’s teenage sketches capture faces and expressions with only a few lines. His paintings as a young man portray young women’s seductive beauty and especially their flowing hair. Christina began to establish herself as a poet, composing In the Bleak Midwinter which we sing at Christmas today: “In the bleak midwinter, Frosty wind made moan; Earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone. Snow had fallen, snow on snow, snow on snow. In the bleak midwinter, long long ago.”

By the 1840s the industrial revolution, political upheavals, and rapid social change were transforming Europe. Gabriel resisted the ”soulless self-reflections” of the Academy, and instead became a central figure in what became the “Pre-Raphaelite Movement”, painting often historical figures in scenes of intense love and conflict – stories of Goethe, King Arthur, Edgar Allen Poe, or the Bible – that resonated with their own lives. Gabriel was particularly drawn to Dante’s Divine Comedy, and many of his later paintings illustrate his contemporary “Beatrice”, Jane Morris. He also adopted Dante’s name as his own: “Dante Gabriel Rossetti.” Christina joined her sister Maria to live and work in an Anglican settlement house for “fallen women,” where the sisters became vocal advocates for women’s rights and social reform. The Tate exhibit was an intimate journey through the lives and choices of the Rossetti siblings at a transformative period in life and art.

Over our Levantine “tapas trio” dinner on our last evening in Britain, I reflected that Gabriel, while sympathetic to the women he “deflowered”, continued to choose his models from among the vulnerable working classes, the shopgirls or seamstresses who, once “ruined”, filled the “fallen women’s home” where his sisters worked; and that the birth control pill had been a true game changer for our generation, stripping the rigid moralists and church fathers of their pejorative labels.

And so, at the end of 21 days, we returned with 115 new miles on our walking shoes, many photos, and so, so many good memories. It’s a treat to see our 3 weeks recreated in the slide show Rick prepared.